Tumores neuroendócrinos do pancreas

Introdução

A incidência dos tumores neuroendócrinos do pâncreas está crescendo, possivelmente devido à realização com maior frequência exames de imagem e à qualidade destes exames. No entanto, sua prevalência felizmente ainda é rara. Esse post do Endoscopia Terapêutica tem a finalidade de servir como um guia de consulta quando eventualmente nos depararmos com uma dessas situações no dia a dia.

Conceitos gerais importantes sobre tumores neuroendócrinos do trato gastrointestinal

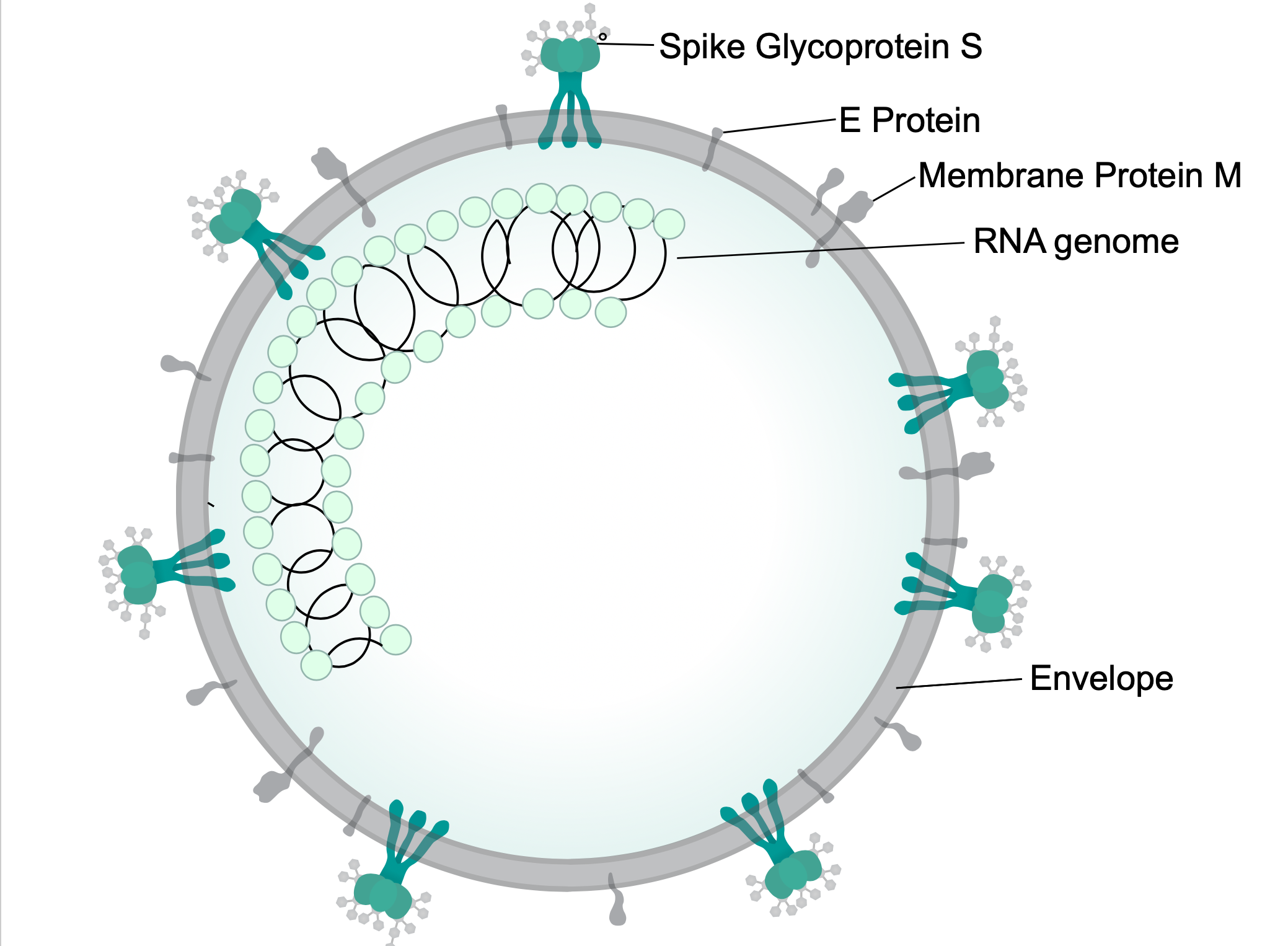

Os TNE correspondem a um grupo heterogêneo de neoplasias que se originam de células neuroendócrinas (células enterocromafins-like), com características secretórias.

Todos os TNE gastroenteropancreáticos (GEP) são potencialmente malignos e o comportamento e prognóstico estão correlacionados com os tipos histológicos.

Os TNE podem ser esporádicos (90%) ou associados a síndromes hereditárias (10%), como a neoplasia endócrina múltipla tipo 1 (NEM-1), SD von Hippel-Lindau, neurofibromatose e esclerose tuberosa.

Os TNE são na sua maioria indolentes, mas podem determinar sintomas. Desta forma, podem ser divididos em funcionantes e não funcionantes:

- Funcionantes: secreção de hormônios ou neurotransmissores ativos: serotonina, glucagon, insulina, somatostatina, gastrina, histamina, VIP ou catecolaminas. Podem causar uma variedade de sintomas

- Não funcionantes: podem não secretar nenhum peptídeo/ hormônios ou secretar peptídeos ou neurotransmissores não ativos, de forma a não causar manifestações clínicas.

Tumores neuroendócrinos do pâncreas (TNE-P)

Os TNE funcionantes do pâncreas são: insulinoma, gastrinoma, glucagonoma, vipoma e somatostatinoma.

Maioria dos TNE-P são malignos, exceção aos insulinomas e TNE-NF menores que 2 cm.

A cirurgia é a única modalidade curativa para TNE-P esporádicos, e a ressecção do tumor primário em pacientes com doença localizada, regional e até metastática, pode melhorar a sobrevida do paciente.

De maneira geral, TNE funcionantes do pancreas devem ser ressecados para controle dos sintomas sempre que possível. TNE-NF depende do tamanho (ver abaixo).

Tumores pancreáticos múltiplos são raros e devem despertar a suspeita de NEM1.

A SEGUIR VAMOS VER AS PRINCIPAIS CARACTERÍSTICAS DE CADA SUBTIPO HISTOLÓGICO

INSULINOMAS

- É o TNE mais frequente das ilhotas pancreáticas.

- 90% são benignos, porém são sintomáticos mesmo quando pequenos.

- Cerca de 10% estão associadas a NEM.

- São lesões hipervascularizadas e solitárias, frequentemente < 2 cm.

- Tríade de Whipple:

- hipoglicemia (< 50)

- sintomas neuroglicopenicos (borramento visual, fraqueza, cansaço, cefaleia, sonolência)

- desaparecimento dos sintomas com a reposição de glicose

- insulina sérica > 6 UI/ml

- Peptídeo C > 0,2 mmol/l

- Pró-insulina > 5 UI/ml

- Teste de jejum prolongado positivo (99% dos casos)

GASTRINOMAS

- É mais comum no duodeno, mas 30% dos casos estão no pâncreas

- São os TNE do pâncreas mais frequentes depois dos insulinomas.

- Estão associados a Sd. NEM 1 em 30%, e nesses casos se apresentam como lesões pequenas e multifocais.

- Provocam hipergastrinemia e síndrome de Zollinger-Ellison.

- 60% são malignos.

- Tratamento: cirúrgico nos esporádicos (DPT).

- Na NEM 1, há controvérsia na indicação cirúrgica, visto que pode não haver o controle da hipergastrinemia mesmo com a DPT (tumores costumam ser múltiplos)

GLUCAGONOMAS

- Raros; maioria esporádicos.

- Geralmente, são grandes e solitários, com tamanho entre 3-7 cm ocorrendo principalmente na cauda do pâncreas.

- Sintomas: eritema necrolítico migratório (80%), DM, desnutrição, perda de peso, tromboflebite, glossite, queilite angular, anemia

- Crescimento lento e sobrevida longa

- Metástase linfonodal ou hepática ocorre em 60-75% dos casos.

VIPOMAS

- Extremamente raros

- Como os glucagonomas, localizados na cauda, grandes e solitários.

- Maioria maligno e metastático

- Em 10% dos casos pode ser extra-pancreático.

- Quadro clínico relacionada a secreção do VIP (peptídeo vasoativo intestinal):

- diarréia (mais de 3L litros por dia) – água de lavado de arroz

- Distúrbios hidro-eletrolítico: hipocalemia, hipocloridria, acidose metabólica

- Rubor

- Excelente resposta ao tratamento com análogos da somatostatina.

SOMATOSTATINOMAS

- É o menos comum de todos

- Somatostatina leva a inibição da secreção endócrina e exócrina e afeta a motilidade intestinal.

- Lesão solitária, grande, esporádico, maioria maligno e metastatico

- Quadro clínico:

- Diabetes (75%)

- Colelitíase (60%)

- Esteatorréia (60%)

- Perda de peso

TNE NÃO FUNCIONANTES DO PÂNCREAS

- 20% de todos os TNEs do pâncreas.

- 50% são malignos.

- O principal diagnóstico diferencial é com o adenocarcinoma

TNE-NF bem diferenciados menores que 2 cm: duas sociedades (ENETS e NCCN) sugerem observação se for bem diferenciado. Entretanto, a sociedade norte-americana NETS recomenda observação em tumores menores que 1 cm e conduta individualizada, entre 1-2 cm.

TNE PANCREÁTICO RELACIONADOS A SINDROMES HEREDITARIAS

- 10% dos TNE-P são relacionados a NEM-1

- Frequentemente multicêntricos,

- Geralmente acometendo pessoas mais jovens.

- Geralmente de comportamento benigno, porém apresentam potencial maligno

- Gastrinoma 30-40%; Insulinoma 10%; TNE-NF 20-50%; outros 2%

- Tto cirúrgico é controverso, pq as vezes não controla a gastrinemia (tumores múltiplos)

PS: Você se recorda das neoplasias neuroendócrinas múltiplas?

As síndromes de neoplasia endócrina múltipla (NEM) compreendem 3 doenças familiares geneticamente distintas envolvendo hiperplasia adenomatosa e tumores malignos em várias glândulas endócrinas. São doenças autossômicas dominantes.

NEM-1

- Doença autossômica dominante

- Predispoe a TU (3Ps): Paratireóide; Pituitária (hipófise); Pâncreas,

- Geralmente de comportamento benigno, porém apresentam potencial maligno

- Gastrinoma 30-40%; Insulinoma 10%; TNE-NF 20-50%; outros 2%

- Tto cirúrgico é controverso, pq as vezes não controla a gastrinemia (tumores múltiplos)

NEM-2A:

- Carcinoma medular da tireoide,

- Feocromocitoma,

- Hiperplasia ou adenomas das glândulas paratireoides (com consequente hiperparatireoidismo).

NEM-2B:

- Carcinoma medular de tireoide,

- Feocromocitoma

- Neuromas mucosos e intestinais múltiplos

Referências:

- Pathology, classification, and grading of neuroendocrine neoplasms arising in the digestive system – UpToDate ; 2021

- Guidelines for the management of neuroendocrine tumours by the Brazilian gastrointestinal tumour group. ecancer 2017,11:716 DOI: 10.3332/ecancer.2017.716

Como citar esse artigo:

Martins BC, de Moura DTH. Tumores neuroendócrinos do pancreas. Endoscopia Terapêutica. 2022; vol 1. Disponível em: endoscopiaterapeutica.net/pt/assuntosgerais/tumores-neuroendocrinos-do-pancreas